The Pyramid Builders at Al Sufouh Road

One midsummer’s day in 2004 I found myself navigating the far end of Al Sufouh Road. This is the main local-access road running through what is sometimes called the New Dubai. Starting from the famed Burj Al Arab (hotel ala seven stars) it runs parallel to the coast of the Arabian Sea. After passing the entrance to the man-made Palm Jumeirah island it continues on to the Dubai Marina. Here it separates the man-made waterside development from a wide coastal stretch of beach and the soon to be completed Jumeirah Beach Residences (JBR)—a megalithic project consisting of some 40 high-rise towers.

One midsummer’s day in 2004 I found myself navigating the far end of Al Sufouh Road. This is the main local-access road running through what is sometimes called the New Dubai. Starting from the famed Burj Al Arab (hotel ala seven stars) it runs parallel to the coast of the Arabian Sea. After passing the entrance to the man-made Palm Jumeirah island it continues on to the Dubai Marina. Here it separates the man-made waterside development from a wide coastal stretch of beach and the soon to be completed Jumeirah Beach Residences (JBR)—a megalithic project consisting of some 40 high-rise towers.If you build it...

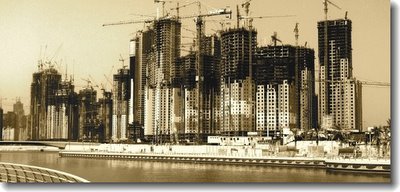

On that hot day in mid-2004 the JBR towers had already begun to sprout, along with other towers on the Marina side of the road. The scene was that of a massive construction site, eclipsed only by the even more massive site that exists today. I fail to recall the purpose of my journey, but it was nonetheless fascinating to see all that was coming up. Like many at the time, however, I had some doubt as to whether Dubai could really pull it off. Its ambitious building schemes, impressive as they were, could not simply by their emergence assure the second half of that oft-quoted equation: ~they will come!

As I began getting lost about the several road diversions I started to wonder further, not whether such projects could be built but whether they should be built. The scale of it all seemed to rival other great construction works past and present. Why is it, I thought, that the desert in these parts had remained so unpopulated until the discovery of oil? The obvious answer was that climatic conditions were just too harsh. So, what had really changed that it should become inhabited by so many today?

As I began getting lost about the several road diversions I started to wonder further, not whether such projects could be built but whether they should be built. The scale of it all seemed to rival other great construction works past and present. Why is it, I thought, that the desert in these parts had remained so unpopulated until the discovery of oil? The obvious answer was that climatic conditions were just too harsh. So, what had really changed that it should become inhabited by so many today?Well, the climate certainly hadn’t changed but technology and the new wealth within the region could support whatever visions one might have for a new city or a new society.

The current construction boom in some senses mirrors earlier booms that in recent decades had already given the cities of Abu Dhabi and parts of Dubai and Sharjah modern and expansive skylines. Like the pyramid builders millennia earlier, human labor as well as ingenuity could be summoned to build great monuments even in the harsh desert climate.

The Question

So, it had already been demonstrated that new cities could be built in the desert. More than 3 million people were already living in the cities of the UAE. But it wasn’t so much a question of whether people could comfortably live and work in the towers and homes already there or in those to come. The question really was with regard to the laborers, those who would dig the trenches, pour the concrete, erect the scaffolding, and install the plumbing, electrical and cooling systems. How much easier would it be for them to toil in the harsh desert climate than it was for, say, the pyramid builders of long ago? Or conversely, if in fact laborers had managed to get through earlier building booms, why couldn't they get through the current one?

A Dangerous Quartet

To start with, it seems things really are different this time. The towers that line the roads of central Abu Dhabi today (the first city in the UAE to experience a major construction boom) are generally around 20 storeys. While it is one thing to build a handful of towers that rise higher than these it is another to erect literally hundreds.

In addition to the singularly tall Burj Dubai tower, presently rising up to 160 floors, there are at least three other towers proposed or under construction in Dubai that are to exceed 100 storeys. The JBR towers alone represent a single project of some 40 towers rising 30 to 50 floors, all being erected within a span of two years. In addition to towers (some sources indicating over 600 under construction or proposed), tens of thousands of villas are buing built, along with eventually hundreds of kilometers of new and expanded highways and roads, tunnels, bridges, massive airport expansions and rail projects. All of this in addition to off-shore reclamation works creating numerous islands and on-shore dredging projects to create and expand lakes and rivers.

In addition to the singularly tall Burj Dubai tower, presently rising up to 160 floors, there are at least three other towers proposed or under construction in Dubai that are to exceed 100 storeys. The JBR towers alone represent a single project of some 40 towers rising 30 to 50 floors, all being erected within a span of two years. In addition to towers (some sources indicating over 600 under construction or proposed), tens of thousands of villas are buing built, along with eventually hundreds of kilometers of new and expanded highways and roads, tunnels, bridges, massive airport expansions and rail projects. All of this in addition to off-shore reclamation works creating numerous islands and on-shore dredging projects to create and expand lakes and rivers.Were such a scale of development to take place in more temperate climates it would still represent an extreme challenge to the labor force. What exists in Dubai today, however, is a quartet of hazards that can seriously impact the well-being of the work force (and the quality of their work):

- extreme heat for several months of the year

- low standards for worker safety, low wages and poor living conditions

- projects which require new and innovative designs and construction methods

- workers whose training is almost exclusively on-the-job

Asking The Right Questions

That brings me back to the question of should it all be built.

When I posed the question to myself on that midsummer day in 2004 I concluded that developers, builders and buyers should, in addition to asking what can be built, begin to ask themselves about the morality of building palaces on the blood, sweat and tears of manual laborers. I wonder if this question ever comes up in the initial planning phase:

- Is there enough capital?

- Is the project technically feasible?

- Will it sell?

- What will the environmental impact be?

- What will the stress level be on the human workforce?

It is in fact, I believe, a moral issue. Just as one worries about issues of crime, corruption, substance abuse, and the like, one should also think about the morality of using wealth to develop a city or country so extensively. Can’t we do without the tallest building in the world if we consider that doing so might spare the lives of those construction workers who may inevitably suffer or perish due to one or another extreme hazard? What will it be like for workmen erecting scaffolding at the 150th floor or for those securing structures underwater while building the world’s first undersea hotel?

Stand Not in the Way

Stand Not in the WayOne year later, in mid-2005, I found myself joining the ranks of buyers, having been lured by the dream of owning a home in a tower off Al Sufouh Road. Should the pyramids be re-built, I ask myself again—this time with blood on my own hands!

The answer? Let us not stand in the way of human imagination and ingenuity. If they dream to build it--and have the means--then let them try. However, developer, builder and buyer will serve the greater good by asking the right questions, including those of ethical and moral basis:

- What problems and issues will arise for the workforce?

- What can I, the developer, builder or buyer do to address these concerns?

JD Perkins Photoessay

Award-winning photojournalist J.D. Perkins presents artistic and thought-provoking images in his photoessay,

building a dream ~hard labour in dubai

Return to MAG 218 Community homepage.

TAGS: Dubai Marina, foreign labor (foreign labour), labor issues (labour issues), workers rights

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home